Listening's pleasure

What following our ears, enhanced by a habit of recording, can do for our wellbeing.

Read time: 9 minutes.

Listening exercise: 3 minutes.

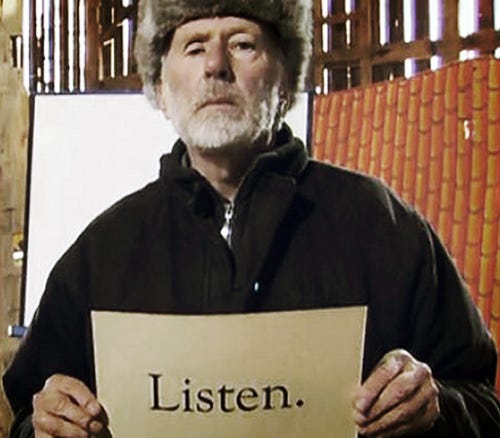

Morning all. In a moment I will ask you, weirdly, to stop reading this. I’d like you to take aside three minutes—if you have them—to stay in a comfortable position right where you are. Standing or sitting, close your eyes (or put an eye-mask on if you prefer) and try to listen to the sounds around you. As you stay there, try to follow your ears:

What information can you gauge from the sounds you hear?

What do the sounds tell you about the geographical location you’re in?

Is there anything about the sounds that suggest a particular time or day?

Begin to focus on each sound individually. How many single sounds can you pick out?

Make a note of each and move on, scanning the space. Do any of the sounds blend into one another? Which ones stand out as totally separate?

Think about each sound’s properties: their shape, texture, pitch. How would you describe them? What materials can you identify from the sounds?

To help, here are some guiding concepts based on the soundscape, courtesy of what should now be a familiar name, R. Murray Schafer:

Keynote – the sounds that are always there in a given space; the ubiquitous hums, the background noise, consistent environmental sounds like wind and traffic that are so embedded into a place that they barely register. Just like the musical key of a song, the keynote is the sound upon and out of which all others make themselves heard.

Sound signal – against the background, these are the “figures” that stand out; bird calls, beeps, bells, chatter, the noisy results of individual actions, these sounds are often listened to in and of themselves, whether passively or actively. Sometimes we’re compelled to listen to them, especially if they warn us of things going on in the environment.

Soundmark – just like a landmark, these are those sounds that in a sense define the acoustic identity of a space. What can you hear in a particular place which tells you it is definitely here rather than somewhere else?

Don’t worry too much about remembering all of these things, but use what you can to guide your listening. Alright… We’re ready to close our eyes and open our ears now. See you in three minutes.

Now, wasn’t that nice? Or maybe you’re bored.

Listening and wellbeing

If that seemed like a mindfulness exercise, it’s because it basically is one. However, it’s also a classic example of the kinds of deliberate listening exercise you’d find in any field recording workshop or sound art meet-up. For this article I drawn loosely from Felix Blume’s collation of listening exercises.

I was introduced to this kind of focused, “deep” listening, using frameworks such as the soundscape, through classes I’ve attended over the years that have usually focused on applying listening techniques to ethnographic research.

But it doesn’t take long to recognise how these kinds of deliberate listening exercises cross over with meditation and mindfulness—of the sort probably lots of you already do, which often includes other strategies like body scanning and that raisin thing.

Now, I’m not alien to the limits of mindfulness as a means to wellbeing, least of all if it’s presented as a revolutionary solution to the strains today’s world presents to the average person.1

Nevertheless, I don’t think it’s controversial to say mindfulness has at least some calming, therapeutic effect. Without going too deep into the matter, taking a few minutes to pay attention to one’s surroundings is an activity that, once you’ve had a bit of practice, simply feels nice. Speaking from experience, when anxiety strikes, taking those three minutes can make a real difference.

I’d suggest that, in an era that Ted Gioia convincingly described the other day as one defined by culture as distraction, the grounding effects of feeling, sensing and being with one’s surroundings is something we could all quite clearly do with right now.

Listening connects

My point here is not just that listening is something that mindfulness involves, but that the ear’s pleasure and wellbeing-related potential is an important reason why anyone would want to go out and deliberately listen, record and share sounds in the first place.

We touched before on the politics and history of doing things with sound, and there’s much more to explore on that front. Often listening and recording has a purpose: we’re listening to.

But for today, let’s consider pleasure itself as good a reason as any for why engaging with the world, the past, and our lives in general through the medium of sound—as AudioSpaces was built to facilitate—is really worth doing.

This isn’t just an individualised phenomenon, either. Listening together seems to not only to bring us more in touch with the spaces around us, but also they provide a social grounding, tapping into a sense of shared acoustic community.

It’s no surprise that the words “listening” and “hearing” in common language have taken on a non-auditory meaning that tend to indicate empathy and connection (take, for example, the phrase “I hear you”).

Deep listening in the everyday

This brings us to one of the amazing lessons I’ve drawn so far from being involved in AudioSpaces. That is—yes, these pleasurable effects we’re talking about can, of course, be done through still, quiet, focused listening in a controlled way—as we got a little taste of a few minutes ago.

But, it’s become much clearer that, at the same time, the same practices can be incorporated into our everyday lives, even on the fly, in conversation, or while doing a whole range of other activities.

Focused, developed listening is something that we can learn to do almost without thinking, and this is where the habit of audio recording may come in handy. Rather than recording to and for something specific, the whole process involved in recording the world is in itself a worthwhile activity.

It might help to consider the idea of “deep” listening, which Pauline Oliveros describes as “the ability to consciously focus attention” through “listening in every possible way to everything possible, to hear no matter what one is doing”.

Oliveros comes from the world of experimental music, drawing from her work with instruments, samples and electronic equipment like microphones. Deep listening bridges her musical orientation to the world with, funnily enough, a kind of consciousness-raising that isn’t dissimilar to mindfulness.

To practice deep listening means being attentive, aware, detailed, open and present. Not only does this exercise the ears in ways useful for the musician, as Oliveros tends to be interested in. It can also have an effect on one’s relations to the spaces, beings and people around us, regardless of your background.

At this point it’s also worth noting a gaping hole in what I’ve been talking about here: listening, pleasure, sound… what about music? Music is probably the most obvious thing that enters our ears to give us (among other things) pleasure, often of the kind that escapes any satisfying explanation.

Music is obviously a worthy category of sound to consider, but what’s more interesting is how that feeling you get from listening to music—and that way you direct your ears and your whole body towards the music you enjoy—can be applied to the acoustic environment more generally.

Our ears are tools

So, deep listening invites us to take a musical attitude to the world. Similarly, AudioSpaces invites us to treat the ear like an instrument, enhanced by audio recording, that can capture and share the sonic world.

Just like the mics on our mobile phones, and the speakers we listen out of, our ears are tools: we are able to re-functionalise them, and re-functionalise them again and again.2

Despite my enthusiasm here, let’s not get carried away. It’s still worth remembering that just like any tool, we can’t be too romantic about the ear, or indeed the microphone. Let’s not even go into the issue with mobile phones—at least for today.

Doing things with sound and audio can lead to more wellbeing, but also the very same things can be painful, manipulative and troublesome. Vibrations can be beautiful, but they can also literally be harnessed as an instrument of warfare.

I can and will bang on about all of this as the newsletter goes on. But at the end of the day, there's always another aspect to listening, especially of the deep, deliberate, mindful kind: following your ears, so often, just feels good.

Now I will do nothing but listen […] I hear the sound I love, the sound of the human voice, I hear all sounds running together, combined, fused or following, Sounds of the city and sounds out of the city, sounds of the day and night [...] Ah this indeed is music—this suits me.

Sources

Felix Blume, ‘Listening exercises’. https://felixblume.com/listeningexercises/.

Jessica Otitigbe, ‘Remembering the Sounds of the World’s Most Iconic Deep Listening Pioneer: Pauline Oliveros’, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 30/15/2016. Link here.

R. Murray Schafer, The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World (Rochester, VT: Destiny Books, 1994 [1977]). Free link here.

Thanks for reading. Sorry for the delay in getting this out again—that’s twice in a month! What a loser. I’m back home as of yesterday, so things should steady up a bit now, give or take life/work circumstances. A literal plague of mosquitos has descended upon where I live at the moment, so fingers crossed I survive that. A warm welcome to all our new subscribers, and everyone who’s downloaded AudioSpaces recently.

Today we’ve continued with this vague theme of introductions, moving from tech history and the politics of audio in previous weeks to the more intimate aspects of listening. Over time we’ll narrow down into more specific themes, especially when you’re introduced to our guest writers and their angles on things. As ever, any suggestions of what we could and should be covering here, as well as any other feedback, is always welcome.

Massive things are going on in the AudioSpaces app right now (make sure you’re updated) and in other parts of the AudioSpaces universe. Keep posted for the February round-up landing in your inbox next week, and check our other platforms in the meantime. Nice rest of the week x

Some of you might remember when mindfulness had its own shiny corporate moment. Silicon Valley execs were boasting their meditation habits, and marketing agencies from Soho to Liverpool Street were offering mindfulness workshops to cover up their awful working conditions. This was indeed quite sickening. The backlash—arguing that mindfulness had become a way of individualising what are ultimately social problems caused by life under capitalism—went round in circles a bit in the Discourse™ sometime around 2017, and continues to be expertly covered by The Mindful Cranks. These days, as the years go on since I first discovered Mark Fisher, I’m to some extent of the view that, at a basic level, if it helps, it helps. There are bigger fish to fry. Like any other technique, mindfulness can be used alongside struggles at a social and political level, just as it can be used to neutralise those struggles. Anyway… I just discovered I can do footnotes on this thing.

In an important way, in modern society, the ear and the microphone aren’t just comparable, but actually exist in a kind of symbiosis—that is, they come together and actually rely upon one another to function. If you’re not sure what I mean by this, keep posted for an article about exactly this topic in the near future.