What audio? Whose map?

Notes on the politics behind the who, the how and the what of recording.

Read time: 12 minutes.

One of the responses I've heard a lot when telling people about AudioSpaces is something along the lines of a nervous "what do I record?".

Obviously the simple, friendly answer is: anything you want. If you're someone who likes to keep things short and sweet, that's probably enough—have a good one; I'll see you in a fortnight.

But as we know, this newsletter here is designed with the uninitiated in mind, and for many people such an answer might seem a little unhelpful. If we're going to invite people to use what feels for many to be a new medium, it's important to provide at least some guidance.

In another sense, we might be able to say that such a response is a bit of a cop out, even dishonest by omission. Because leaving it at "record anything you want" seems to suggest that all sounds, all audio—and all listeners—are equal.

Purporting total freedom assumes that we all come from a common starting point, that we face the sonic world as entirely free, entirely unrestricted. “Record anything you want”, as if every vibration (and every means to record it) just lay there in happy resonance, each one next to the other, ready to be picked and shared with the rest of us.

But clearly we live in a world that isn't, by any means, anything-goes. Such a statement of fact can be applied pretty far and wide, but we can limit it for now to just the audio world. The preferences, trends and techniques that developed around making and remaking audio from sounds “out there” have, over time, turned into norms, rules and hierarchies.

In other words—and only a quick pressing of the ear against the chest of this audible cultural sphere is needed to tell us this—in our world not all audio, and certainly not all listeners, are equal. Stay with me here.

Technology and listening

In his groundbreaking historical work The Audible Past, Jonathan Sterne traces how modern audio technologies developed alongside new ways of listening over the course of the twentieth century.

Sterne talks about a few different examples throughout the book: early recording and listening devices like the phonograph, vinyl, wire and tape machines, the radio, the telephone and even the stethoscope.

He shows that all of these technologies were always partly designed with specific types of listening in mind. At the same time, the listening habits of people were also affected by these very technologies.

You’ll have to read the book to get the grubby details. But by my own reading, what’s important for us here is that we can identify two driving features of twentieth century audio and listening, which completely shape our experience with any kind of audio recording.

On the one hand, there is a favouring of precision and fidelity (things sounding accurately and similarly to their original source) and the development of specialised techniques of listening.

Meanwhile, on the other hand, there is also an interest in a kind of immediate, immersive, pleasurable experience that helps audio to be packaged up as a kind of commodity (something that can be sold as a product).

The mystique of audio

The result is that, all the way up to our current time, a certain mystique has developed around audio that presents it as something specialist on the one hand, and something consumable on the other.

Think of the audio engineer, equipped with monitor speakers designed for utmost clarity and a balance of frequencies. Or the classically trained musician and musicologist, whose acquired tonal ear works perfectly alongside industry-standard microphones used in studio recording.

The conservationist field recorder, with parabolic microphones that allow for the precise analysis of non-human populations. Or maybe the doctor, whose years of auscultation training is only matched by the rigour and specificity of their various medical-grade acoustic equipment and ultrasound scanners.

Then there is the mass of non-specialists, who despite, I'm willing to bet, tending to deliberately and expertly record audio every day (ever sent a voice note? recorded a video?) have been encouraged to see our relationship to audio as one primarily based on consumption.

Of these latter listeners the ordained tools are earphones, the compact formats of packaged sound bites, digital or otherwise, designed to readily immerse yourself into. We expect a certain balance of dynamics, fidelity and stability that is only noticeable when absent (why are airport tannoys always so difficult to understand?).

The music listener, phone caller, film SFX enjoyer: recorded audio, at least we instinctively feel, is always given to us pre-made.

Conversely, tools such as microphones and the like are understood to be the territory of audio specialists: people with access to specific techniques of listening and using technology. Meanwhile, the sounds they were designed to capture become privileged as the ones worth recording within a given field.

We don’t have to get all Michael Gove and reject (or even criticise) the expert, the specialist, or the precise. Not at all—these kinds of listening are essential to our lives, and are often very beautiful. Likewise, the audio the rest of us all consume and the way we consume it is usually pleasurable and effective.

But here's the cracker. Just as much as the techniques and technologies have been built for the uses of specific listeners in mind—whether that's the specialist or the mass listener—the reverse is also true: listening itself, and our understanding of how to listen, to record, to even identify sound, is shaped by those very techniques and those very technologies.

In other words, along with the many benefits that come with the mystique of modern audio is a sense of closure. When rules and hierarchies seem to work well, it’s easy to forget there’s still a world outside of them.

Acoustic conservatism

We’ve covered the “who” and the “how” here, then. But the final piece of the puzzle is the “what”—after all, we’re trying to find blueprints to answer the question “what do I record?”.

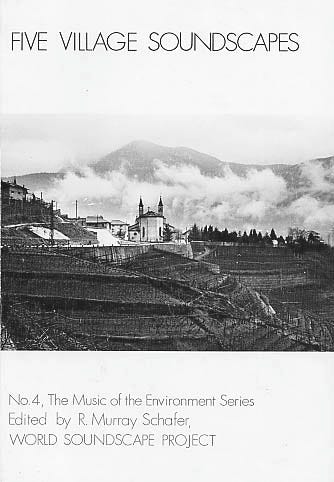

A couple of weeks ago I mentioned acoustic ecology and the soundscape, especially as put forward by R. Murray Schafer and his students. This is a perfect place to start thinking about how, when it comes to recording, certain sounds are clearly valued over others.

Schafer certainly had his own ideas of what should be recorded, related to what he thought were sounds that should literally be saved, to the detriment of others. We mentioned last time his concern with noise pollution, and his desire to save the idyllic "natural" traditional soundscapes of his childhood in rural Canada.

His concern for sonic heritage against unwanted intrusions came at a time when his country, like the rest of the Global North, was changing not just because of new loud machines and speakers, but also in terms of demographics.

The acoustics of his home nation was deeply affected by the movement of people from rural villages into cities, and by the growth of migrant communities with different languages and cultures, coalescing into what would become the urban masses of the mid-to-late twentieth century.

Schafer’s response was a kind of conservatism that looks back longingly to the sounds of the good ol’ country days where these new folk and their *cough* loud customs didn’t exist.

I’m obviously being a bit glib here, and the late Schafer is too complicated and brilliant a figure to be painted as just some old racist. But it’s no wonder that when he travelled around the world to record his soundscapes, he favoured, yes, old traditional European villages. It seems that certain sounds, and indeed certain people, are just more worth saving than others.

It’s easy to see how this might still lie in the DNA of recording practices today, and how a certain hierarchy of values permeates the audio world that favours the “natural”, clean and traditional over the new, the untamed and the messy.

The podcast Phantom Power has a great episode about Schafer which addresses this very topic in much more detail and nuance.

The politics behind the tech

If you’ve stuck with me to this point, good stuff. We’re dipping our toes into a bit of social theory here, which isn’t always easy to get your head around.

What we’re really trying to tease out is that behind all these different technologies, ways of listening, norms and judgements regarding audio, is the workings of power.

This is what I mean by the politics behind audio recording: this isn't the obvious “Politics” of elections, protest and the mostly awful people we see on the news, but simply the workings of power to decide who does what, how, and why.

Everything we’re talking about here applies to maps as well, by the way. It might sound odd at first, but a map is just as much a technology as a microphone or a speaker. In any given map, a set of materials, designs and objectives come together for the purpose, in this case, of representing space in some way.

Just as with audio, certain ways of "doing" maps have solidified over time into rules that don't even seem like they've been made by us anymore. We're so accustomed to the perfectly scalable map used (and obviously very useful!) for navigation, it's easy to forget that maps can represent space in other ways.

Take the medieval Mappa Mundi, one of which you can visit in Hereford (say hi to my grandma if you do). These were in theory maps of the world, but not your average A-Z atlas: their makers weren’t so interested in accuracy of distance or dimension, but instead provided a representation of space more relevant to their time.

This incorporated spiritual and narrative elements into the design itself: Christ at the top, dotted with ancient labyrinths, real places included in symbolic terms rather than to be actually navigated to and from, and even a whole bunch of weird medieval guys.

There are examples of maps, too, that do represent space for navigation—but according to techniques and tools that we might not be used to. Cue Emily Jacobi:

What about a map that can be read in the dark, that floats and suffers no damage if dropped in the sea? This is true of the maps of Inuit people in Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland), who traditionally carve portable maps out of driftwood, which are used for navigating their windy coastal waters.

I give these examples to show that technologies and techniques, even those so naturalised as those that go into making a map, can take different forms when the rules, the priorities and the values are changed. How might we take this perspective to technologies of audio, to techniques of listening and to the question of what to record?

Sound maps in the plural

So now we have an idea of why finding a satisfying answer to the question “what do I record?” opens up a bit of a Pandora's box of power dynamics, histories of use, design and value-judgements regarding sound. What now?

Doing away with, or at least holding in suspicion, the idea of "good quality" audio is a simple first step for us, as we know that what falls under this category can and has changed over time.

Point zero for AudioSpaces is that a simple mobile phone will do for recording our world—although we also can't forget that the technology of the phone itself has a history, including the microphone inside it, designed especially with the transmission of specific *cough* voices in mind. But that's a story for another time.

In terms of deciding what sounds are and aren’t worth privileging on a sound map, there are lots of important efforts to decolonise knowledge about sound, about the practices involved in acoustic ecology and even about maps.

These are often conversations going on in academic and, yes, specialist circles. This isn’t that surprising, as a big part of decolonisation involves changing knowledge from the inside out, not to mention that audio and maps are still fairly niche interests in the grand scheme of things.

But in this newsletter, just as with the rest of AudioSpaces, we want to help unravel that specialist packaging that so often seems to surround audio practice, to make it genuinely accessible.

If we’re going to do any of this, it makes a lot of sense not to blindly repeat the same rules and layers of power that the audio world is still dealing with.

So, right from the start, it’s important that we open up these political conversations as well—not just as an abstract discussion, but as a springboard for thinking more clearly about what we can and want to use AudioSpaces for.

Let’s take the social interests implicit in the so much existing audio practice, the interest in preservation, in memory, in representing, exploring and intervening in space, and definitely its emphasis on creativity, on self-expression.

But let’s also try to always question the value-judgements that come with these things: what’s worth recording, whose ears are worth following, and what counts as “good” audio. Why do I think the things I think when I hear the word “record”?

This is one of the reasons we’ve held off on strictly calling AudioSpaces “a sound map”, even though as we saw in the last post it clearly operates within that universe. Because whose map is it? Perhaps it's best to call it a collection of real, possible and soon-to-be-realised sound mapS, in the plural.

In short, any map (sonic or silent) has it's authors, and decisions will always be made about how each space is represented—the thing that will really help us in working out where we want to position ourselves in that map is to always ask and challenge who is making those decisions, and what are their effects.

Never a non-position

Having said all this, we clearly have an angle and certain personal interests that inevitably go into the way AudioSpaces is designed. Any design involves a set of interests. One of those is, of course, specific sounds that trigger memories, and voices or environments that capture particular moments in space and time.

I also, for example, have my own personal approach, my own favoured microphone setup and a particular taste for sounds that I like to record: usually outside spots, in public squares, parks, or rivers, where different accents of beings human and non-human, machinic rattles, blabber and nature’s rhythms all mix into one. I usually don't include myself in the recording, or at least try to minimise my presence.

I’m admittedly a bit weird though, and my style is just one approach to recording, which has developed through studying and playing with sound for a while.

It would be doubly dishonest to pretend we don't all have our own ideas about what the content of a collective sound mapping project might consist of. But we're eager to be surprised, to be proven wrong about what should be recorded, how and where.

We're even working in-app to allow you to be even more deliberate with your sonic interventions in AudioSpaces, such as the new Collections feature (keep your app updated to try it yourself, otherwise it'll be explained in better detail at the end of the month).

So maybe the answer to the question "what do I record?" is still pretty much that same “anything you want” that we began with. But our takeaway point here is that "anything" is always going to be filtered through history, politics and the power of people to make value-judgements.

Keeping that always within earshot is not only necessary to face those hierarchies that have developed around audio practices; it might just also help with thinking about which sounds are really important to each of us—and why.

Sources

Simon Garfield, On The Map: Why the world looks the way it does (London: Profile Books, 2013).

Mack Hagood, ‘R. Murray Schafer Pt. 2: Critiques & Contradictions’, Phantom Power, podcast, https://phantompod.org/ep-30-r-murray-schafer-pt-2-critiques-and-contradictions/.

Emily Jacobi, ‘Indigenous Cartography & Decolonizing Mapmaking’ in Technology Solidarity, Jun 22, 2020, https://medium.com/technology-solidarity/indigenous-cartography-decolonizing-mapmaking-a6357112d7a7.

Jonathan Sterne, The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003).

Thanks for reading. We hope that, whether you’re a current AudioSpaces user or not, you might find something useful in these articles. As always any comments, ideas and submissions are welcome.

Those of you paying attention will notice that today isn’t Monday, and I’ll apologise here for missing a deadline I actually set myself. Turns out finding consistent enough wifi to format an essay into Substack while travelling isn’t as straightforward as one might think. Or, maybe we could be friendly and say that Thursday is just another name for Monday.

In case you missed it, take a look at all the AudioSpaces goings on from January in our monthly round-up. On the app side of things, more exciting new features and fixes are coming through at lightning speed, so iPhone users: make sure you stay updated.

Great entry, mate. While reading it I recalled a difficult text I read once in one of my seminars “Feld, Steven “From Schiziphonia to Schizmogenesis: on the discourses and commodification practices of “world music” and Worldbeat (1997. Chicago University Press). Sounds has its politics and tech mediates on what and how we record absolutely.