The sound map

We get a feel for the concept and how AudioSpaces fits into it. Also, a list of some of our favourite existing sound mapping projects.

Read time:

Whole article – 10 minutes

Just the top sound maps list – 5 minutes.

By now, if you have any idea of what we’re up to here, it might be that it’s something to do with audio, and that it involves maps. And… you’d be correct.

One of the main things that AudioSpaces does is take these two things which most of us do every day with our phones—record audio and navigate maps—and squishes them together.

Our driving idea is that sharing sonic moments from our everyday lives on a map has unique potential for unlocking and preserving memories, and we’ll be exploring why that is a lot here in the newsletter.

First things first, it’s worth asking what actually is the AudioSpaces app? What’s it for? What are its precedents? Our influences?

The basics

The basic idea of combining “audio” and the “space” isn’t in itself original. Rather, our project can be partly thought of as the latest contribution to the ongoing history of the sound map.

The easiest way to define a sound map is that it’s a map, obviously, that has audio clips uploaded and tied to individual locations on the map. They’re usually accessible online, and they’re often (though not always) in some sense collaborative.

People can browse and listen to the audio on the map, but they can also often add their own recordings themselves. Apart from that, each project generally has its own set of unique features, purposes and limits.

But I would suggest that every single sound map—no matter how different—has a few things in common: they use audio to represent spaces, they have an interest in saving, exploring and recovering the past, and they are creative endeavours.

If this point is all you get from this article, I’m happy. You’ve understood one important (but not the only!) aspect of AudioSpaces, at least how I see it. But if you’re still wondering where all this comes from and why, then it’s worth going back a bit.

If you’re not in the mood for a even tiny bit of history, feel free to scroll down a bit and jump straight to the list of top sound maps to explore.

(A partial) origin story

The sound map has its roots in the crossovers between art, public education and collaborative research. Actually, there are a number of different histories that could be told here (there always is) with starting points all over the world.

The different origins of the sound map draw from interests as disparate as monitoring endangered rainforest species, collecting oral histories, acoustic urban planning and even sharing samples, bleeps and bloops for art and early electronic music.

We’ll probably untangle all of this in future posts. But a useful place to start is acoustic ecology: a set of practices emerging in North America in the late 1960s, concerned with the way humans affect, and are affected by, their acoustic environments.

Pioneering figures here were R. Murray Schafer, Barry Truax and Hildegard Westerkamp, all of which worked together developing the field through the World Soundscape Project (WSP) at the Simon Fraser University in Vancouver.

These artist-researchers went about recording the sounds around them in increasingly systematic ways, coining new categories to describe industrial, urban, rural, non-human and geological types of acoustic phenomena.

They drew from their backgrounds, usually in musical composition, to carry out field recordings (outside in the world, away from the studio). They’d analyse the audio they captured, save it in massive archives of tapes and records, and then re-present the sounds to the public in a variety of creative ways.

The soundscape

One of those ways was the soundscape, of which you probably have a rough idea. For now we’ll go with the Acoustic Ecology Handbook’s definition:

An environment of sound (or sonic environment) with emphasis on the way it is perceived and understood by the individual, or by a society. It thus depends on the relationship between the individual and any such environment. The term may refer to actual environments, or to abstract constructions such as musical compositions and tape montages, particularly when considered as an artificial environment.

The soundscape is, then, a way of representing spaces (real or imaginary), based on how they are heard by people, put together using audio recordings.

Right from the beginning the soundscape always involved the goal of having a social impact. The idea wasn’t just to record the sonic environment, but to make people listen and be aware of their own soundscapes—with the ultimate hope of affecting (or, for them, improving) it.

For example, Schafer was obsessed with noise pollution in modern cities. He had it in for the loud roar of the industrialised world, and the new ubiquity of traffic, crowds and electronic speakers, which he felt radically interfered with our traditional relations to “natural” acoustic space.

He even wanted compulsory “ear cleaning” for school children—which is a bit weird to be honest, but a story for another time.

Against that pesky noise pollution, attention was turned to “saving” our sonic heritage. In other words, rescuing those older sounds that were being replaced and drowned out by the modern world.

They loved a bit of church bells, meadow birds, river mills, village markets (nice, but maybe a bit old and stuffy if you ask me). They physically stored these recordings as large libraries of soundscapes, while they also made different kinds of visual interpretations of what they heard.

Soundscapes were also always thought of as creative things—the WSP was made up of mostly artists, after all. From the 1970s, audio equipment has been good enough (and increasingly cheap enough) for artists to begin playing around with their recordings of acoustic environment.

From then on, you could pretty easily go out and record a sound, slap it into a tape machine (nowadays a computer), and then bend, stretch and mix the audio into completely new, often otherworldly creations.

From soundscape to sound map

Why are we talking about this? For me, this brief history of acoustic ecology tells us a lot about the what’s and the why’s of the sound map. If we’re part of the sound map’s history, maybe you could call this a pre-history of AudioSpaces.

In the soundscape we find a new way of collecting and organising audio recordings, and an interest in using that audio to represent spaces. We find the will to impress upon the practice of recording a social cause, to share audio with the world in order to change the way people perceive their environment—and, maybe, to change that environment itself.

We also have a focus on somehow saving the past, on archiving old sounds and memories. Finally, there’s a creative drive: an interest in experimenting and collaborating to make something new with sounds.

These, friends, are all the raw ingredients of a sound map. All that remained to be done was put it all together and make it interactive.

If we jump to the 2000s, enter the tools needed to do exactly that: digitally navigable maps, affordable computers, the internet, mp3s and wavs and so on. This might have been a shift for the acoustic ecology could do, but it’s been an even bigger one for maps.

Think about the classic map: grids and jagged lines, coloured patches and shapes, names, codes and bendy arrows, all of which for however many centuries and millennia were stuck silent on scrolls, books and folded paper, then digitised, scrollable and expandable on screens. It was (almost) always a visual medium, but now with sound maps they speak out to us.

So, for those of you who weren’t quite sure of the idea when you first heard about AudioSpaces, this little introduction to the sound map, with its (partial) origins in acoustic ecology and the soundscape, will hopefully help.

Top sound maps to explore

We’re not exactly sure what AudioSpaces is in its entirety yet, but it’s definitely got a foot in the sound mapping universe. We’ve taken inspiration from a few different places, and amongst those there are some great examples of sound maps. Here are a few of our favourites.

radio aporee

Most definitely the big daddy of online sound maps. A perfect example of that blend between art and research, with an obvious interest in environments and acoustic ecology. Started by Udo Noll in 2006, aporee is global in scope, with audio uploaded from pretty much any place you can think of.

Best used on a desktop, the emphasis on “good” quality recordings means the listening experience is almost always silky and nice, and can be genuinely useful for acoustic research. But at the same time, it can be a bit intimidating—and perhaps limiting—to those who aren’t dedicated field recordists. Which is fine!

There’s a lot of fun to be had, though, listening to different places from around the world, especially with the “geomixer” play function. This lets you blend and create virtual journeys by layering audio on up to four different channels, quickly turning into a surreal, cacophonous—yet subtly musical—soundscape built from different acoustic worlds.

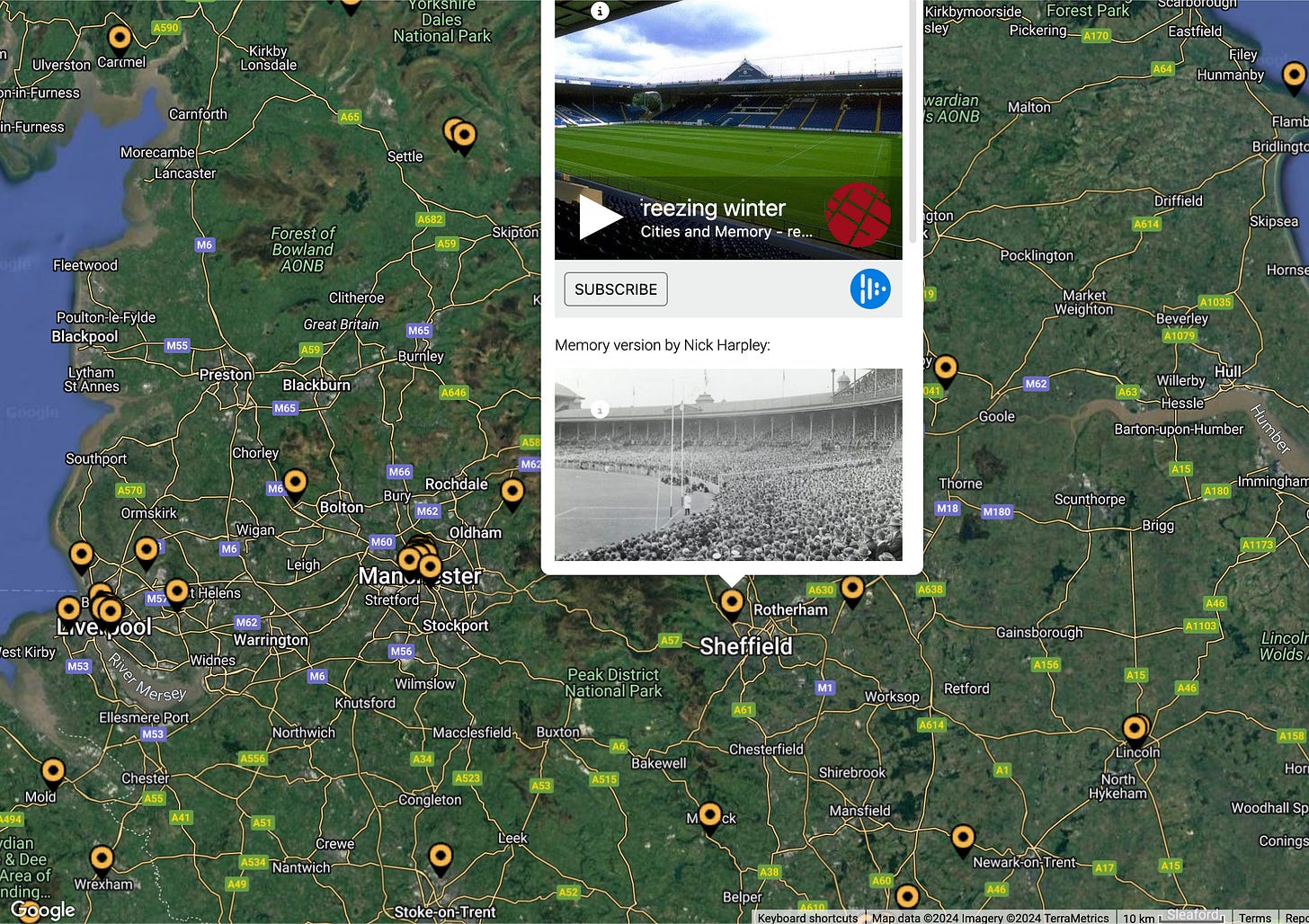

Cities and Memory

A massive, collaborative sound mapping project founded by Stuart Fowkes. Expertly designed and broad in scope for those intrigued about how things sound around the world. Listen to a mountain peak in the Dolomites, a jazz bar in New York, a protest in Bogotá, songs at a food market in a rural Ugandan village and then an ocean cliff in Bali, all in one sitting.

Although it’s open to submissions and collabs, the map is very curated. Every audio clip has its raw version, and a remixed “memory” version. This makes an art or music piece out of the recording, reimagining the space as an ambient delight.

Dialect and Heritage Project

When we talk about saving sounds from the past, with capturing and showcasing our sonic heritage, some projects do that very explicitly. Based on two massive surveys of English dialects done in especially in the 1950s, you find a treasure trove of accents and short oral histories of rural people from around the country.

It’s fascinating listening to some of these; even though the recordings are only from, at most, seventy years ago some of the voices sound totally alien, their accents barely comprehensible to my ears at least.

Filled with stories of these people’s lives, beliefs, cultural traditions, the map is full of little windows into a near past that somehow still feels really distant, even though it’s so local (assuming you’re English!).

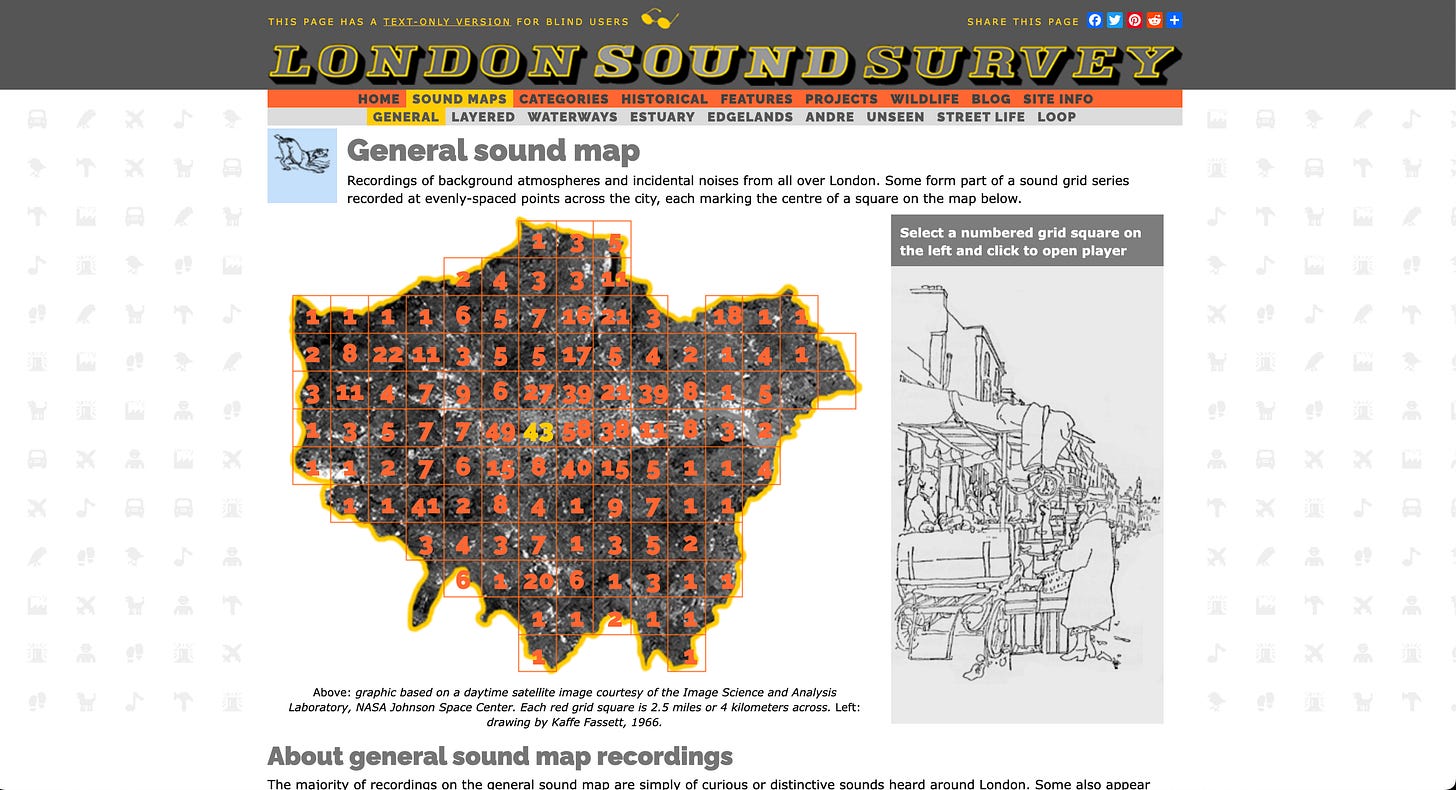

London Sound Survey

Another one close to home for me, but so well put together that it should be of interest to anyone. The London Sound Survey recorded everyday life in the British capital from 2008 to 2020. The actual project is, in a sense, completed now, so it’s not open for new submissions.

However, along with all the background research and genius sample design, there’s so much to explore if you’re into the city. The real beauty of this one is the multiple clever ways the different sounds, different moments, different places are categorised, divided, put into relation with one another. Even if you’re a dedicated life-long Londoner you’ll discover things you’ve never heard of.

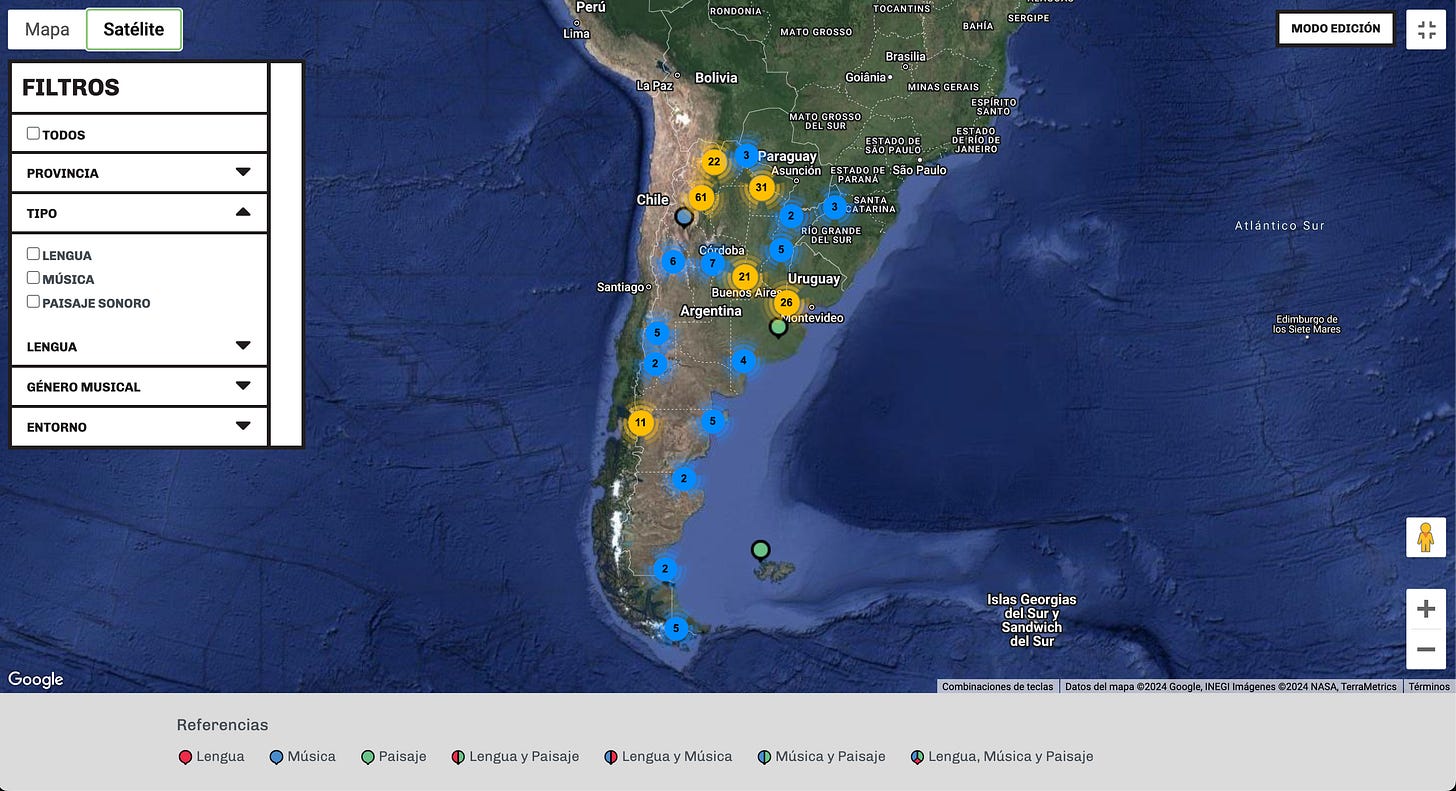

Sonidos y Lenguas

This one’s just Argentina, but it’s another creative example of a sound map that reveals the rich and layered heritage of a place, this time organising it into three general categories of audio: recorded speech, recorded music and soundscapes. It’s really nicely executed, with lots of auxiliary information, podcasts, ongoing research (all in Spanish at the moment I’m afraid).

It might seem a bit rogue to include in the list an example from Argentina, of all places. Partly this is because Dylan, who’s writing this (hey), lives there and has had contact with the lovely people from the SyL project. I’m such a fan that you’ll very likely hear more about this project.

But also, when it comes to writing about technology, audio (and even maps!), there’s still a bias towards Europe and North America in general, and the English-speaking world in particular. It’s important to try to always highlight other perspectives, as an ethical principle, even if it’s just in small ways like this.

In that spirit, here are some other examples for us to turn our eyes and ears away from Euro-Anglo-America: Sono Mapa (Costa Rica); Mapa Sonoro de México; Mapa sonoro comarca andina (Argentina); Mapa sonoro (Peru); Soinu Mapa (Basque country); Ecouter Le Monde (global, but emphasising the Francophone world); Mapa Sonoro Curitiba (Brazil). Loads more here.

Echoes

It has gotten a lot of attention in the audio and sound art communities, and I can confirm that the Echoes app is very cool. A mobile-only app that allows you to create and highly localised, immersive sound maps can change as you move—otherwise known as sound walks.

Interestingly enough, the concept of the sound walk originates in the work of Hildegard Westerkamp, of the World Soundscape Project that we discussed earlier.

The app is smooth and attractive, with options to go on free and paid walks which range from heritage guides to even interactive fictional narratives. Actually creating your own walks is a bit of a task, so it’s not really a thing that you can contribute to in your everyday life but rather a special way of interacting with specific locations.

Radio Garden

A final gem; rather than share and listen to uploaded audio clips, this map allows you to listen live to an impressive amount of radio stations around the world. Here we’re faced with a whole additional aspect: the simultaneity of radio. That is, you can be listening to the same broadcast at the exact same time as who knows how many other people.

This surely affects our relation to spaces, the map giving us the instant ability to entangle ourselves with listeners across distances far and wide. On the other hand, as it works with live radio it isn’t really an audible archive like the other sound maps—but to be fair, it doesn’t claim to be.

Sources

Samuel Thulin, “Sound maps matter: expanding cartophony”, Social & Cultural Geography, 19:2 (2018), 192–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2016.1266028.

The World Soundscape Project website. https://www.sfu.ca/sonic-studio-webdav/WSP/index.html.

Citys and Memory, ‘The top ten sound maps’, 28 July 2015. https://citiesandmemory.com/2015/07/top-sound-maps/.

By the way, for the nerds, if you don’t have library access but want to read further, give us a shout and we’ll happily send you any of the materials we use that sit behind a paywall. That goes for now and anything we publish in the future… just shhhh...

Dylan x

That’s all for now; thanks for reading. Our next few posts will continue with the theme of introductions, where AudioSpaces came from, what we’re on about, etc.

As well as our regular articles, stay tuned for our weekly Traces micro-series of sonic nostalgia: short vignettes submitted by our friends and the wider AudioSpaces community.

Don’t forget to follow us on TikTok and Instagram for some sweet and dreamy audiovisuals, and a reminder that our survey is still up and running. Finally, of course, if you have an iPhone or Mac give the AudioSpaces app a download and get recording.