Read time: 13 minutes.

I’ve said it before: one of the reasons this newsletter exists is to try to figure out what AudioSpaces is and can be. This mental task isn't only to give ourselves direction in our own project designs—although it certainly helps.

Rather, having an open conversation about what we are and what we want to do with the app is also a way of bringing you lot with us. After all, the multiple maps and audible archives that make up AudioSpaces is built between everyone involved, collectively and collaboratively. So it’s only right that we think out loud about this.

We nevertheless announced in February that we’d move on towards more specific topics, paying special attention to the theme of wellbeing. It turns out, though, that the question “what is (or can be) AudioSpaces?” is quite an important one when thinking about our own relation to wellbeing. So let’s indulge ourselves in self-reflection just one last time.

We need to talk about how we can ensure that AudioSpaces makes life better for us, not worse. And in the spirit of reflection, we probably also need to think about why this is an issue worth talking about in the first place, to lay out the stakes—which will be the focus of this first part. To do all this, we’re going to have to make a couple stop-offs along the way. A good place to begin is with something I always hear when I mention this thing I’m involved in called AudioSpaces.

“So, it’s a bit like Instagram but with sounds?”

Uhhhh, ok. Fair enough, you can see where this idea comes from. We do have some similarities with the basic format of Instagram and those other web-based phone apps that we’ve over time come to lump together as “social media”.

Make your personal Profile and Subscribe, Follow your Friends and Explore their Posts; regularly check your Feed to Discover what’s being Shared. Sound familiar?

I’m being glib here; I hope you’ve already assumed that we’re not going to directly follow in the footsteps of TikTok, that horrible place which used to be called Twitter, or anything associated with Meta.

Yet, we do indeed share some of these terms, quite simply because they describe well how to navigate the app. We shouldn’t be surprised here. This social media language—which is so naturalised now, it’s easy to forget that the way we use these words is actually quite new—seems to have become, at some point in the last decade or so, the default framework for making and consuming culture online.

We could reasonably boil AudioSpaces down to two things: the capacity to build your own personally-curated, publicly-available archive of recorded audio, and connectivity between users. The app lets us both record what we want and share those very recordings between us. To produce, consume and distribute sounds and spaces, all using the same tool.

I think this—alongside our emphasis on making audio practices accesible to the non-specialist—is what sets us apart from other online sound mapping projects.1 It’s not that we’re going out of our way to make a new social media site, but the very logic and designs that make AudioSpaces possible exist in a framework shared, in some cases formulated, by social media apps we all know so well.

This seems intuitively true—otherwise no one would ever posit the question I started with. But how? Where does this framework come from, and how have we slipped into it, perhaps without even noticing?

Convergence

I’m old enough to remember, albeit vaguely, the announcement of the original iPhone in 2007. Steve Jobs, in his signature black turtle neck-blue jeans combo, paces smugly in front of a black Apple logo so big and epic it’s pictured blocking the sun. He’s describing all the groundbreaking steps he and his bros have already made for global culture and communications, from online communications with the Macintosh in 1984 to music consumption with the iPod in 2001.

Then quickly comes the real announcement. In one single product, they’re going to “revolutionise” three media forms: IT communication, music listening and the telephone. He repeats, to the nerdy joy of Apple fans in the crowd, these three media one after the other again and again, until it’s clear that the revolution he’s speaking about isn’t just a major improvement of all three, but a merging of them into one device—into the iPhone.

What’s going on here has a lot to do with what Henry Jenkins calls media convergence: what he claims is the general direction that media and culture has gone in modern societies, especially since the development of digital technology. Convergence is characterised by an ever-accelerating “flow of content across [and between] multiple media platforms”. Once separate locations of culture become, in other words, increasingly overlapped.

Jobs isn’t just showing off that Apple has combined three technologies into one device: he’s providing a model—basically instructing us—to think of the internet, the phone, and music listening in a new way. Now they’re to be conceived of, and used, together.

The smart phone was by no means the beginning of this kind of media convergence (and the iPhone was not the first smart phone), but looking back on it now it certainly seems like a landmark acceleration. Our phones quickly became, only within the last fifteen or so years, the site in which all media occurs, bounces around and transforms. Bring “social networking” (like what Facebook was originally for) into the mix, and soon by the 2010s, so-called social media becomes the principal manner in which convergence takes place. And along comes our rumoured ocular cousin.

Instagram, we might say, reconfigured the medium of photography to become not just something truly massive (as in, a medium not just for photographers but of mass culture, which Kodak had largely already done decades before), but something fully integrated into the connectivity of other media online. It also, crucially, turned photography into a practice closely linked to socialising and individual identity.

I’m not necessarily interested in the convergence of different technologies itself right now—even though without that, of course, none of this is possible. What matters more in the discussion of social media is the cultural logic that comes along with this melding of images, sounds, videos, internet communication and so on, within the same device.

Social media apps make use of the phone’s in-built convergence to mix you with the things you make, share and consume. They blend our social lives and our social selves with art, with marketing, with commentary, with our political views and conflicts, our personal insecurities, our creative practices and our impulses for entertainment.

This is now the framework within which we make culture and the way we consume it. Everything is connected, shareable (and to be shared), cross-platform, hyperlinked, embedded, to be saved to and displayed on your profile, sent via messages. With Instagram, photography is also now a way to catch up with your mates, to show off, to flirt, to self-promote your work, to reinvent oneself, and to nosy about other people’s lives.

In terms of media forms and technologies that were once totally separate converging into each other, AudioSpaces at least in theory seems to be swimming down the same stream as the photography-portfolio-phonebook-meme app and its associates. This logic might be, then, a key ingredient for understanding what makes AudioSpaces even possible. It makes sense that people would, at first glance, think of our idea as Instagram with sounds; we operate within a culture of convergence, which has already long taken its final form as “media, but social”.

Anyway, it’s all nice and well chatting about media theory, but can you see where this is going? If you remember, we’re thinking about the topic of wellbeing here. If AudioSpaces shares its genetic makeup with social media, then… perhaps, do we have a problem on our hands?

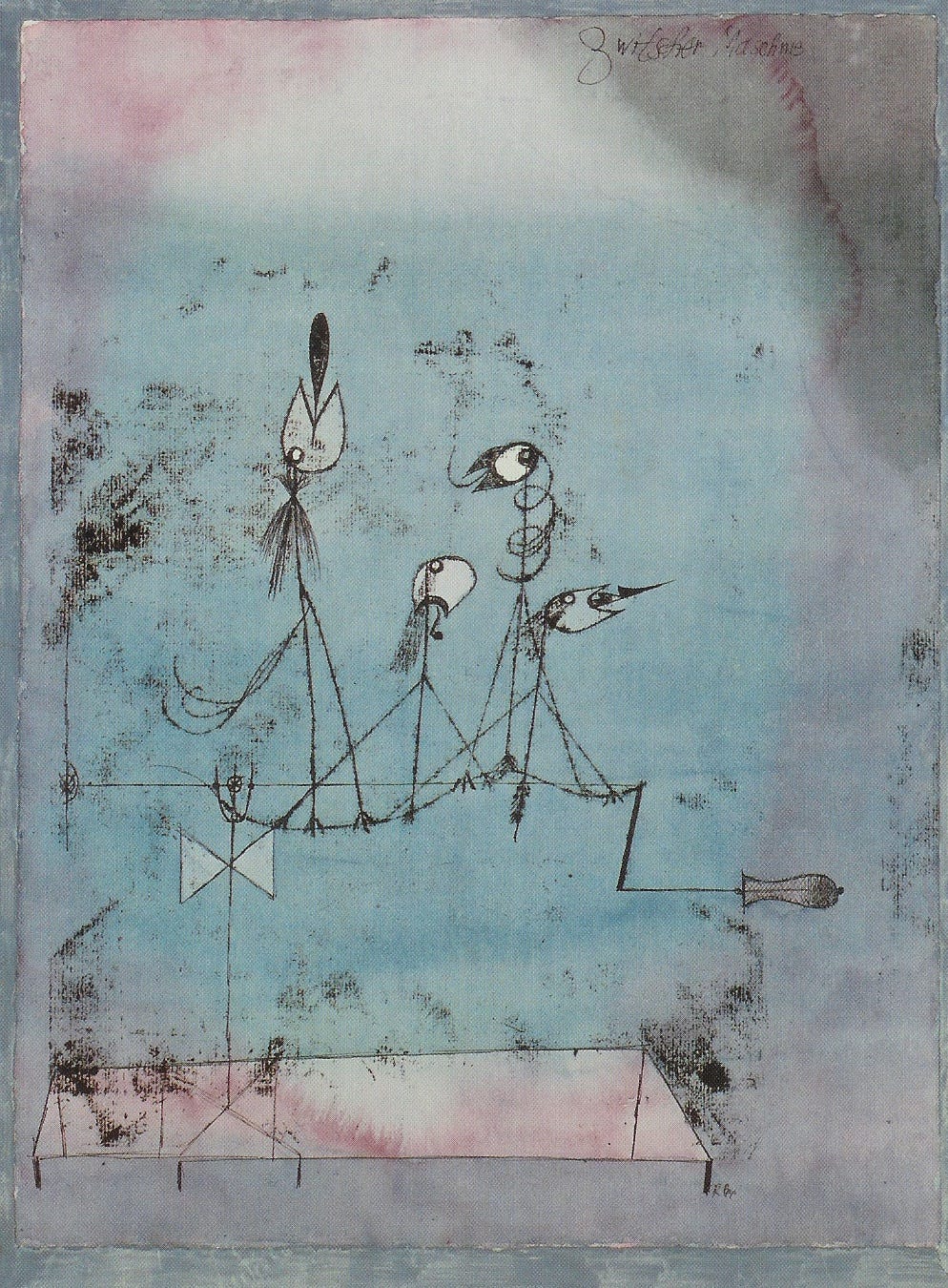

The Twittering Machine

Public conversation has, for a long time now, been awash with talk of the damage that modern technology—and especially social media—wreaks, both on our personal health and on that of society at large. The series Black Mirror, especially before it moved to California and lost some of its British TV Grit, reveals the various evils and vices that could easily emerge from the screens in our pockets.

It should be a familiar story to most of us now. First there was an almost quaint optimism in the early 2010s, when Twitter catalysed the Arab Spring; when we could all suddenly message our grandmas, argue about socialism with strangers, share Futurama memes and swap our fresh new Ableton beatz all on the same couple of tabs (just me?); and when there was at least a perceived sense of vibrant creativity and democracy of opinion happening on these websites.

This gave way, slowly but surely, to a set of common attributes that we closely associate with social media in 2024: addiction and anxiety, troll factories, bots, fake news, as well as a variety of spiralling routes into neurosis, vanity and low self-esteem. In The Twittering Machine, Richard Seymour is characteristically bleak about it all:

If the social industry is an addiction machine, the addictive behaviour it is closest to is gambling: a rigged lottery. Every gambler trusts in a few abstract symbols – the dots on a dice, numerals, suits, red or black, the graphemes on a fruit machine – to tell them who they are. In most cases, the answer is brutal and swift: you are a loser and you are going home with nothing. The true gambler takes a perverse joy in anteing up, putting their whole being at stake. On social media, you scratch out a few words, a few symbols, and press ‘send’, rolling the dice. The internet will tell you who you are, and what your destiny is through arithmetic ‘likes’, ‘shares’ and ‘comments’.

This book came out in 2019, and social media has arguably gotten even weirder and more chaotic since then, but the trend is basically the same. What was supposed to be a highly connected, participatory media environment has seen most of us become a lot more isolated, and disconnected from the world around us, than we had been before.

There’s a parallel conversation also going on about the social media effect on culture itself. The production of culture increasingly happens on, for and through these platforms. As within the logic of social media this “content” becomes linked to connectivity, comments, views—the “numbers”—becomes the incentive for producer becomes increasingly one of maximising engagement.

This applies to writing and art (First Floor’s assessment of what’s happening to electronic music is a great example here) but also to any cultural producer, including all of us who contribute, comment and share stuff on these sites. The format steers us into making things for clicks, to jump on trends, to game the algorithm—both in the actual contents of what we make, and in the sense of a growing compulsion to constantly “create”.

This is a double-edged sword, then, where both at the level of production and of consumption, what we spend our time engaging with stops being meaningful media but rather becomes more a never-ending culture of distraction. This is partly what is meant by the so-called “enshittification” that seems to take hold of each social media site as they enter they final zombified incarnations—have you been on Facebook lately? More on this in part two. Even Substack, the self-proclaimed antidote to social media, seems to be falling into the same cycle.

The obvious question is, then: why is this happening?

Well, clearly a big part of it is the fact that social media is, as Seymour names it, a social industry. For the corporations that own these platforms—especially now they’ve long gone public and are thus behold to their shareholders—our wellbeing means, well, nothing really. The only real priority is extracting more and more value out of the product in order to squeeze more and more profit out of the thing. In this case the product is our own engagement, which is sold to advertisers. Neurosis and addiction is thus required to keep us scrolling, and quantity of clicks always trumps quality of content.

So, as with most things: capitalism. Unfortunately, this is the mode of production we live under at the moment. And even worse in the case of most of these companies, it’s poorly regulated, shareholder, California tech, surveillance capitalism.

However, this describes the context in which social media emerges—not the form that it takes, or the logic by which it works. More immediately consequential for us here is less the capitalist need for value extraction, but rather the actual media architecture itself, not only in technological sense, but also how we all think about and use it. For me, the logic of convergence goes a long way to explaining precisely why culture online has become this big old cortisol party—which we’re all invited to, and ultimately all implicated in.

Let’s not get too carried away

That all sounds a bit dire, doesn't it?

Well, before we go any further, let’s roll things back a tiny bit. Firstly, as stressful as things can get, it’s also true that these tools have had bewildering, impressive effects on our lives and on culture. There’s no going back to photography, film, music or other art forms being isolated from one another, nor to media being fundamentally separated from audiences or from our own senses of self & identity.

Things are blended and meshed now, and there ain’t no un-meshing—and I’m not sure I’d want there to be. Rejecting things entirely and trying to go directly backwards seems just as wrong-footed as being blindly techno-optimistic. The useful thing is to be honest, thoughtful and critical, which is our task with this newsletter.

Second, as you can probably guess, for me the social media apps we know and use are already a lost cause. But we’re concerned with AudioSpaces here, and it’s not clear we can assume audio recording, listening and sharing online is something that would ever have the same effects as its image and text equivalents.

Is there not something just inherently more artificial about photos, more narcissistic about writing? Is there not something more patient, considered, and less neurotic, about a practice (recording audio) that requires before anything else listening? By isolating the “second sense” in what we’re doing with AudioSpaces, are we perhaps already avoiding ‘gramisation from the outset? These are questions I don’t have a real response to just yet.

So, why is this an issue worth thinking about then? After all, there’s not much point in complaining or spreading doom for no reason, especially about things that we all basically already know. One of the things that distinguishes our current era from the one most of us (90s babies and above gang) grew up in, is that things generally feel like they’re getting worse, not better. It doesn’t do much good to talk about this just for the sake of it.

What’s more, I obviously wouldn’t be writing this newsletter at all if I didn’t think AudioSpaces was worth our time. Yet building an app and a project that we hope to be enjoyed by lots (and lots) of people comes, naturally, with a sense of responsibility. As I suggested in a previous post, recording—as an activity that comes with and enhances listening—can make us feel good. But what if all of a sudden it doesn’t?

My response is that convergence is still just a cultural logic, not a force of nature. This gives us some room for manoeuvre. Whether any media or technology is good or bad for us always depends on a combination of how it’s built and how we use it. And luckily for us, we have the privilege of being able to think about—and affect—not only use, but design as well.

As Jenkins insists, one aspect of convergence that it tends to involve “people [taking] media into their own hands”. We ultimately get to decide whether we make sure AudioSpaces continues to make us feel good—or whether we eventually, well, become shit. I’d suggest that we can avoid the nefarious designs of our Silicon Valley neighbours if we’re critical about how we go about things. What this critical practise might involve is exactly what we’ll cover in part two.

Sources

Henry Jenkins, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide (New York: NYU Press, 2006). Read the introduction here.

Richard Seymour, The Twittering Machine (London: Indigo Press, 2019).

Thanks for reading. This is our first post that takes a step away from talking strictly about audio recording, coming at AudioSpaces from a different angle. Hopefully, though, it’s still of some interest and use to your own journeys with sound and the tools to explore it—whatever form these may be taking right now.

The best way to let us know how it’s all going for you is by contributing to and exploring AudioSpaces itself. We also always love your comments and messages on any of our platforms.

What’s more, if you’re tempted, we’re keen for people to get involved in any number of ways. This could be both in cyberspace and in the great outdoors: for example by working with us on a Featured Collection, collaborating with us in events, and of course writing for this very newsletter. Maybe all three! Nice week peeps.